Greg Hodson1, Eric Wilkes2, Sara Azevedo1 and Tony Battaglene1

1 – FIVS, 18 rue d’Aguesseau, 75008 Paris, France

2 – Australian Wine Research Institute, Hartley Grove, Urrbrae SA 5064, Australia

Abstract

This paper examines the origins of methanol in grape wine and the quantities typically found in it, as well as in other foods such as unpasteurised fruit juices. The toxicology of methanol and the associated regulatory limits established by competent authorities in various parts of the world are also considered. It is concluded that such limits are not driven by public health considerations and thus authorities are requested to consider the need for methanol analyses to be performed and reported on certificates of analysis as a condition of market entry for wine. Where methanol limits are still deemed to be necessary to achieve policy objectives, authorities are encouraged to establish them in the light of the levels of methanol typically found in grape wines produced by the full array of internationally permitted winemaking practices, and to consider harmonising their limits with those that have already been established by other governments or recommended by appropriate intergovernmental organisations.

© The Authors, published by EDP Sciences 2017

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

- Introduction

The origin and significance of methanol in wine, and the associated establishment of regulatory limits for its presence there, are causes of much confusion and misunderstanding in international trade. This paper, produced by the FIVS Scientific and Technical Committee, reviews the topic in some detail, providing reference materials to assist with further study. It concludes that the levels of methanol commonly found in grape wines are broadly similar to those that may be found in many freshly squeezed and unpasteurised fruit juices if they are stored for a period of time after squeezing. It is further demonstrated, from a comparison of regulatory limits for methanol in wine with food safety risk assessments that have been conducted by reputable bodies, that the limits themselves do not serve any real food safety purpose. This is because many litres of wine per day or even per hour would need to be consumed (even if the product contained the highest content of methanol permissible in regulations) to even approach intake levels of any known toxicological concern [1].

2. Chemical properties and other information for methanol

Methanol is chemically characterized as follows [2]:

2.1. Chemical Formula, Synonyms, CAS Registry number

Chemical formula: CH3OH

Synonyms: Methyl alcohol, Carbinol, Wood alcohol

CAS Registry Number: 67-56-1.

2.2. Physico-chemical properties

Physical appearance: Methanol is a colourless liquid with characteristic odour.

Melting Point: –98 °C

Boiling Point: 65 °C

Solubility in water: Miscible.

3. Origin of Methanol in wine

3.1. Action of pectinase enzymes

3.1.1. Action of endogenous pectinase enzymes on pectin in grapes

Methanol is produced before and during alcoholic fermentation from the hydrolysis of pectins by pectinase enzymes (such as pectin methylesterase) which are naturally present in the fruit. More methanol is produced when must is fermented on grape skins; hence there is generally more in red wines than in rosé or white wines (see Sect. 4 below).

3.1.2. Use of exogenous pectinase enzymes in winemaking

Exogenous pectinase enzymes are permitted for use in winemaking (generally as clarifying agents) in at least the following countries: Australia, Canada, the 28 Member States of the European Union, Japan, the Republic of Georgia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States. Their use is also deemed to be an acceptable winemaking practice by the International Organisation for Vine and Wine (OIV) [3]. As with the activity of pectinases naturally present in grapes, the use of exogenous pectinases as a winemaking practice will have the effect of increasing the levels of methanol in the resulting wine.

3.2. Treatment of wine with Dimethyldicarbonate

Dimethyldicarbonate (DMDC) is an effective pre-bottling sterilant, accepted for use in winemaking in Argentina, Australia, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, the 28 Member States of the European Union, the Republic of Georgia, Hong Kong China, Myanmar, New Zealand, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and the United States, whose use is generally limited in international regulations and recommendations to a maximum treatment of 200 mg/L of wine [4]. For other alcoholic beverages and mixtures of alcoholic and other beverages with an alcoholic strength by volume of less than 15%, the limit on usage is often set at 250 mg/L. The use of DMDC can be important in stabilizing lower alcohol products from additional fermentation in the bottle, and also allows a reduction in the quantity of sulphur dioxide that is used where the oxygen in wine is kept below 1 mg/L. DMDC breaks down rapidly in wine, producing carbon dioxide and leaving methanol at very low levels not harmful to health and other innocuous products in the wine. Methanol at a level of about 100 mg/L is created in wine from a DMDC treatment at the typical maximum treatment level of 200 mg/L [5].

4. Typical levels of methanol in wine

It was noted above that the presence of low levels of methanol in wine is expected due to the action of pectinase enzymes that are naturally present in the grapes. A study of the literature indicates the following information concerning the typical levels of methanol that may be found in wine (these levels generally do not account for any additional amount that may result from a DMDC treatment):

• Red wines will tend to contain more methanol (between 120 and 250 mg/L of the total wine volume) than white wines (between 40 and 120 mg/L of the total wine volume), because of the longer exposure to grape skins during the fermentation [6].

• Wines made from grapes that have been exposed to Botrytis cinerea (e.g. late harvest wines, such as Sauternes or Tokay) also have higher methanol levels than standard grape wines (as much as 364 mg/L of the total wine volume) [7].

• Wines made from non Vitis vinifera grapes tend to contain more methanol than wine from pure Vitis vinifera [8].

4.1. Case study: Typical levels of methanol in Australian wine

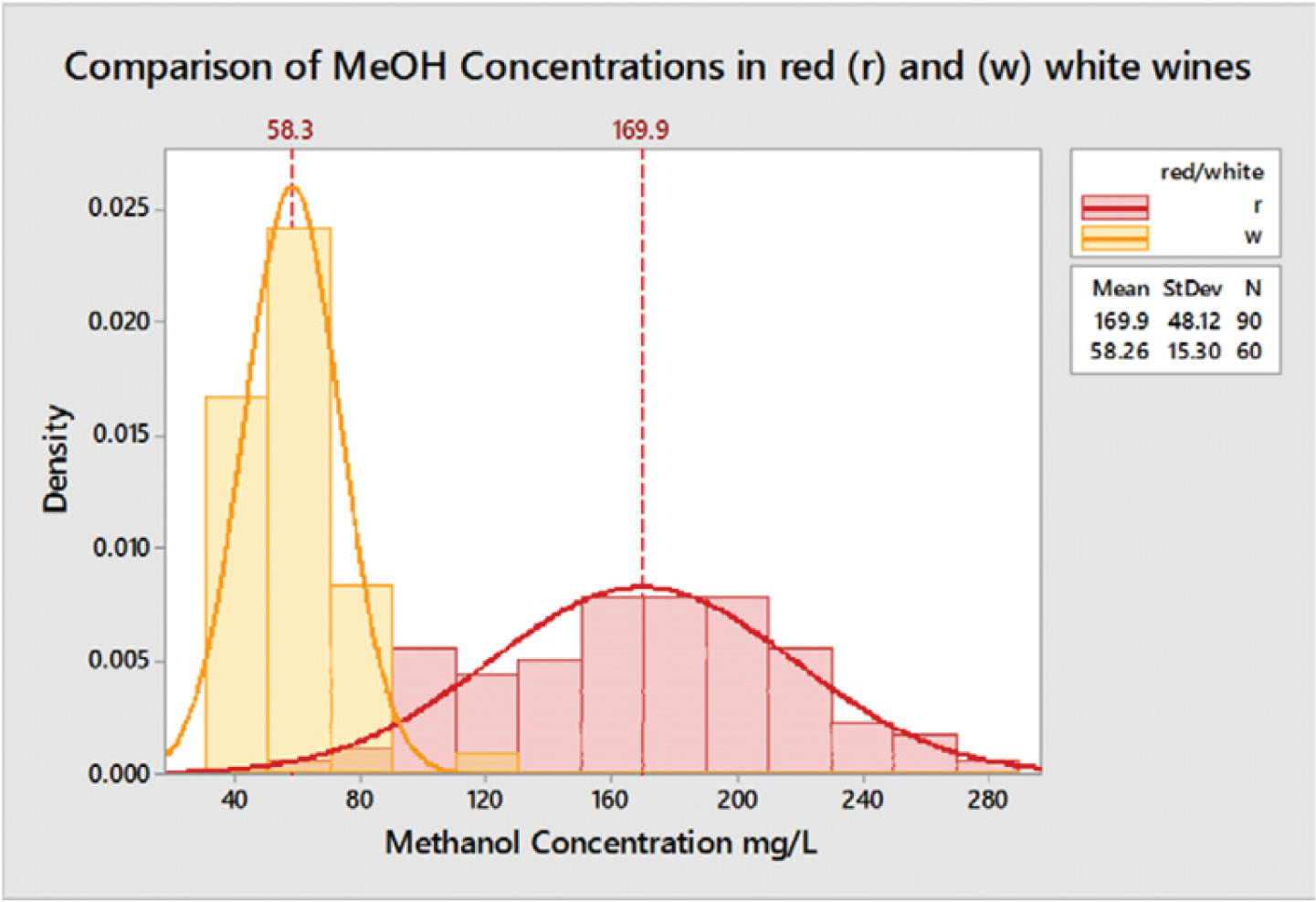

A recent survey looked at 150 wines from across Australia to determine typical levels of methanol in commercial wine [9]. The sample set consisted of 90 red and 60 white wines from multiple varieties and vintages. All wines were analysed using a GC-FID in the Australian Wine Research Institute’s ISO 17025 accredited laboratory. No evidence of DMDC treatment (a source of methanol) was found for any of the wines tested.

Typical ranges for methanol found in Australian wines were; 60–280 mg/L in reds (mean 170 mg/L) and 40–120 mg/L in whites (mean 58 mg/L). All wines tested had some methanol content. The main driver for higher methanol levels appeared to be skin contact during processing. Variety or vintage had no significant impact.

4.1.1. Typical values

Results for red and white wines were significantly different. Red wines typically contained higher levels of methanol across a larger range of content, reflecting greater variation in skin contact times. All wines were found to be within Australian and OIV guidelines (Fig. 1).

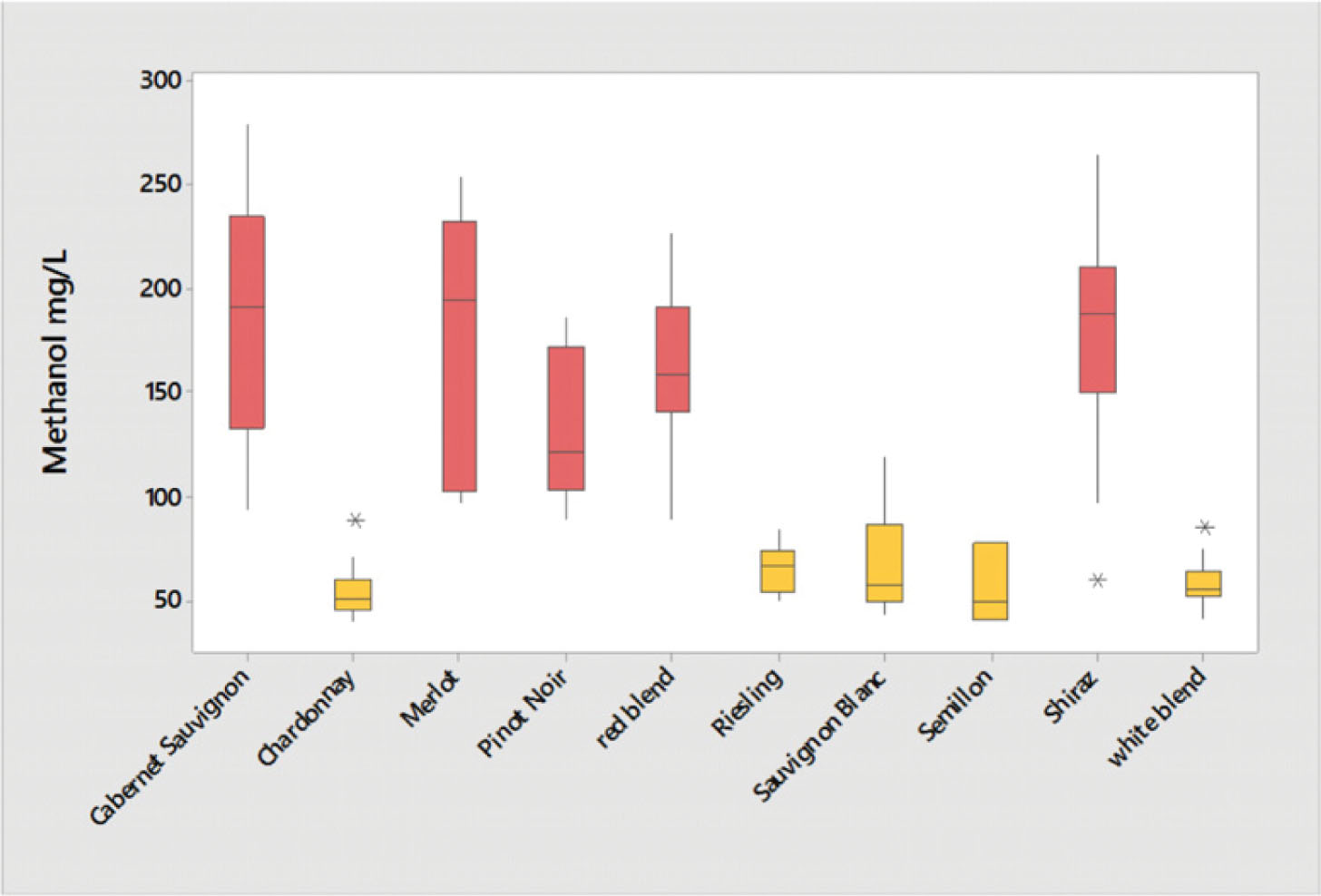

4.1.2. Impact of variety

No significant differences of methanol content were found based on grape variety. The only difference found was between red and white wines, reflecting the differences in processing for the different wine styles (Fig. 2). 4.1.3. Impact of vintage

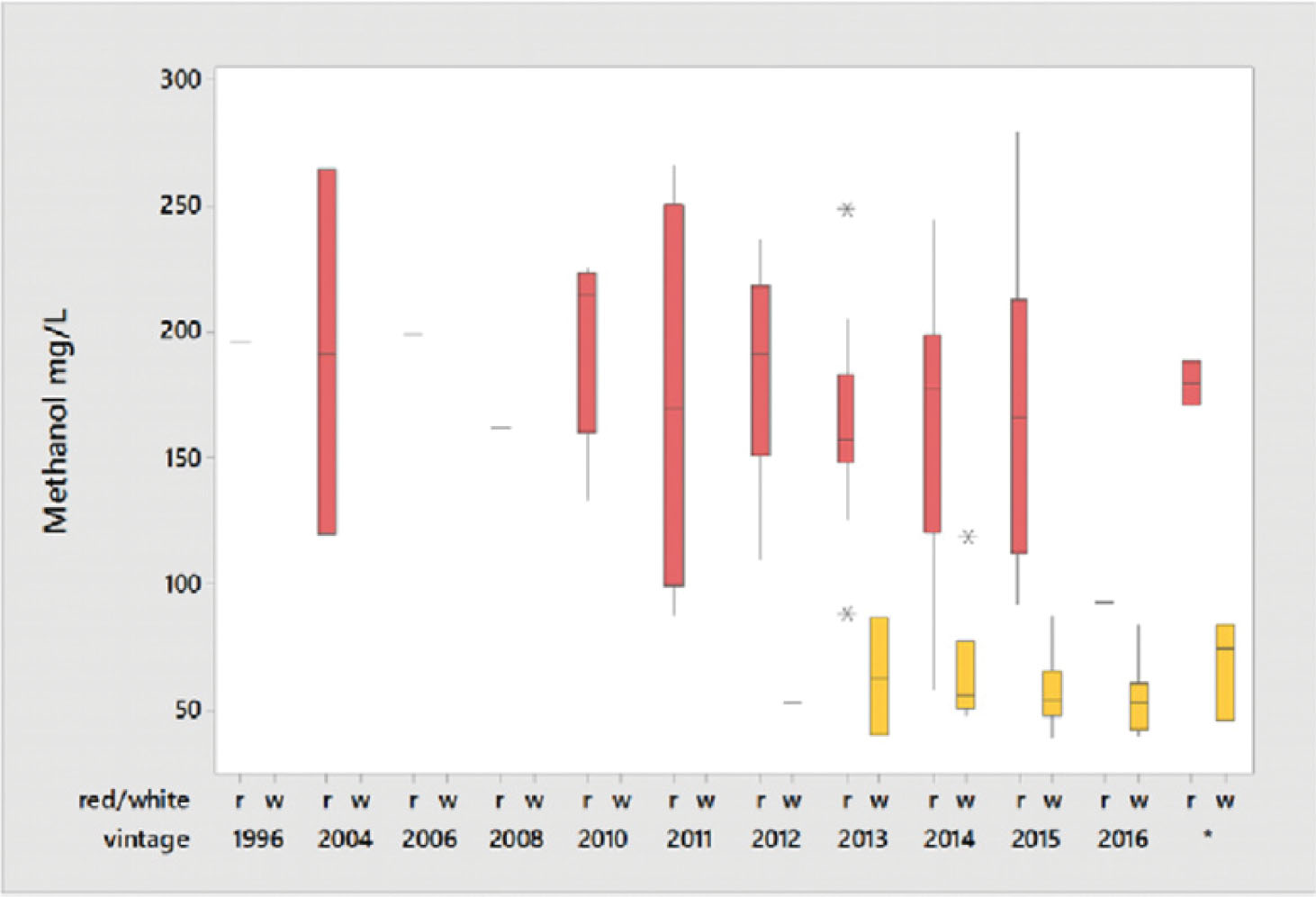

4.1.3. Impact of vintage

No significant impact of year of production on the methanol concentration was found (Fig. 3).